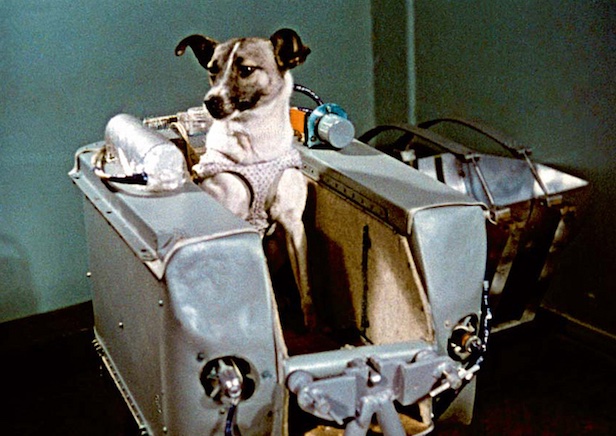

On April 11, 2008, a sculpture was unveiled in front of the Russian Cosmonaut Training Center in Moscow. The figure in the statue depicted a cute dog standing on a rocket. Symbolizing a belated homage, this statue took us back to the early years of our space history. With its journey on November 3, 1957, the story of Laika, which made history as the first living being to go into space, brings deep sadness.

Sputnik, the first spacecraft to leave the Earth, was also the first step in a new and long era. The Russians scored the first goal in space exploration, which resembled a match between the Soviet Union and the United States, with Sputnik 1. Just before November 7, the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Soviet Union, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev thought it would be very meaningful to send a second space shuttle. The order cuts iron. Since it did not seem possible to bring forward the work on the current shuttle (later called Sputnik 3), the decision to start a new project was made in haste.

Khrushchev ordered his engineers to produce a shuttle that would consolidate the superiority created by the first satellite and achieve a new “first,” which was unjustifiable. In preparations for human-crewed flights, Soviet scientists had been toying with the idea of experimenting with animals for some time, and the goal for Sputnik 2 was now clear.

The decision was taken to place a dog on board the second satellite, and the development of a new vehicle began. In the experiments launched in 1951, 12 dogs were put through a series of tests during flights in the upper layers of the atmosphere.

The problem was, however, that after Khrushchev gave the order, only five weeks remained for the launch. At that time, the necessary vehicle had to be designed, built, and the launch planned and tested. In addition, the space shuttle’s passengers would be found and trained.

The inevitable reality was that the necessary tests of the spacecraft’s components would be done differently. History would be made with a rushed project. Moreover, Sputnik 2’s only mission was not to take a living being into space. Objectives such as gathering information about solar radiation and cosmic rays were also written on the mission sheet for this shuttle.

AN ORDINARY STRAY DOG

Three dogs were trained for the Sputnik 2 flight: Albina, Muska, and Laika. Over 20 days, the dogs were kept in cages that were made smaller and smaller each week to help them acclimatize to Sputnik 2’s confined space. In these cages, which offered very little space, the dogs were generally restless and refused to relieve themselves. Their condition was worsening, and laxatives were not helping. The researchers then decided to make the dogs’ living space a little larger. Even so, they were unable to move except to sit, stand and feed. For dogs accustomed to constant movement, this became even more unbearable. The dogs were subjected to long periods of training with a centrifugal machine that simulated the acceleration of the space shuttle and devices that helped them get used to the noise. During this process, the dogs’ heart rate doubled, and their blood pressure increased by 30-65 torr. The dogs were also acclimatized to their food in space, a high-nutrient jelly-like food.

Oleg Gazenko, a Russian scientist researching life in space, chose Laika for this mission and took a close interest in her training. From an ordinary stray dog wandering the streets of Moscow, Laika’s fate was changed by a process entirely against his will. Soviet scientists often preferred to use stray dogs for such difficult missions because they were resistant to extreme cold and hunger. Laika, a 6-kilogram mongrel female, was about three years old. During the preparation process, Soviet scientists nicknamed the dog Kudryavka, which means “little curly” and called her by this name. Laika (spelled Лайка in the Russian alphabet) was a name like “Karabaş,” a name commonly used for dogs in Turkey. In the United States, newspapers combined the name Sputnik with the word “mutt”, meaning mongrel dog, and referred to the dog as “Muttnik”. According to Soviet sources, Laika was a cross between a Siberian husky and a terrier. Laika had a calm character, did not fight with other dogs, got along well with people and loved to play.

SPUTNIK 2 ON ITS WAY

As the days and weeks passed quickly, the technical team was busy developing the vehicle. Using elements from the other extensive project underway, engineers were taking measures to ensure Laika’s survival in the shuttle. An oxygen generator was installed on board to absorb carbon dioxide. A cooling system was also added to keep the dog’s living space cool by automatically starting up when the cabin temperature rose above 15 degrees Celsius. According to the calculations, food was also provided to feed the dog during the seven-day flight. A large container for storing its feces was also provided. Laika would be attached to the vehicle with a specially designed seat belt. These belts prevented the dog from moving except for sitting, standing and lying down. There wasn’t much room to move around in the cabin anyway. The installed equipment would monitor the animal’s heartbeat, breathing frequency, blood pressure and movements.

A JOURNEY WITHOUT A RETURN TICKET

At the time of Laika’s space mission, almost nothing was known about the effects of space travel on living beings. According to some scientists, it was impossible for humans to live in space conditions. Engineers therefore concluded that it was necessary to send animals into space instead of humans for the first test mission. Sputnik 2, however, was not designed to return to Earth. It was therefore certain that Laika would not survive the mission. At the time, neither in the Soviet press nor in other countries did the ethical side of the issue come up much. There was only talk about Laika’s departure, no one talked about the aftermath.

This was a source of great sadness for the project team. The intensity of the four-week preparation process strengthened the bond between the team members and Laika. Shortly before the launch of Sputnik 2, one of the experts on the program team, Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky, took Laika home. In this cozy home, Laika played with Vladimir Yazdovsky’s children before the mission of no return. In a book published many years later, Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky had this brief but moving quote about that day: “I wanted to do something nice for him, he had so little time left to live.”

THE LONG SLOPE TO SPACE

On October 31, 1957, three days before the launch, Laika was placed in the shuttle for trials. Before the launch, two experts were assigned to observe Laika’s every moment. Just before liftoff at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, Laika’s fur was meticulously soaked in a mild alcohol solution. The areas where the receivers that would report bodily functions would be placed were also smeared with tincture of iodine. Since the climate at Baikonur was quite cold at the time, a hose connected to a heater supplied warm air to the dog’s cabin.

Finally, the moment arrived. With the sensors in place, Laika’s every reaction could be measured. From the first moments of the launch, Laika’s breathing frequency increased three to four times, significantly as the shuttle accelerated. Sensors showed that his heart, which was beating 103 times a minute before the launch, was beating 240 times a minute in the first moments of acceleration. After the shuttle approached orbit, Sputnik 2’s nose piece was successfully ejected, but the so-called “Block A” piece failed to separate as planned, preventing the thermal control system from functioning properly. Due to some damage to the heat-insulating parts, the cabin temperature rose to 40 degrees Celsius. After three hours in zero gravity, Laika’s heartbeat had returned to normal. Initial measurements showed that Laika was nervous, but still ate his food. But seven hours after the launch, there were no more vital signs from the shuttle.

FIRST LIVING BEING TO GO INTO SPACE AND DIE IN SPACE

The exact cause of Laika’s death remained a mystery for a long time. In 1999, it was reported that Laika died on the fourth day of the journey as a result of overheating in the cabin. Dr. Dimiti Malashenkov, a scientist on the Sputnik 2 team, explained in a 2002 paper that Laika died 7 hours after the launch due to overheating and stress. “It was practically impossible to come up with a reliable temperature control system in such a limited time,” Malashenkov wrote in a paper presented to the World Space Congress. After five months and 2570 orbital revolutions, Sputnik 2 left orbit on April 14, 1958, with Laika’s lifeless body on board. Laika became the first living being sent into space by the USSR to orbit the Earth and die in orbit.

In any case, the experiment proved that a living passenger could survive in the space shuttle and in the zero-gravity environment once in orbit. Before the launch of manned flights, this first experiment paved the way for scientists to learn how living organisms would react to the space environment.